Narwhal

CLASS: Mammalia

ORDER: Cetacea

SUBORDER: Odontoceti

FAMILY: Monodontidae

GENUS: Monodon

SPECIES: monoceros

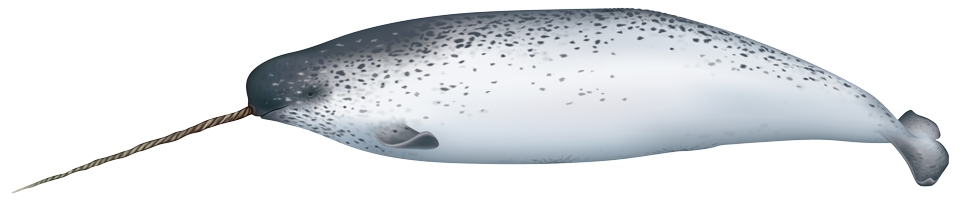

The narwhal is a medium-size odontocete, or toothed whale. Some people think that its long, spiral tusk is the source of the myth of the unicorn. It has a thick layer of blubber and no fin on its back, which make it possible for the narwhal to live in the extremely cold waters of the Arctic and to move freely under ice. While usually seen in groups of 20-30 animals, sometimes narwhals form groups of up to 1,000 during their migration. The narwhal, beluga, and the bowhead are the only whales that spend their entire life in the Arctic.

Physical Description

The narwhal is a chunky, stocky whale, with a small rounded head. Its most distinctive feature is its long tusk, which may grow to be nine feet long. The narwhal only has two teeth. In most females the teeth never erupt through the gum. In most adult males the right tooth remains embedded in the gum while the left tooth erupts through the front of the jaw and grows as an elongated tusk. This tusk always grows in a counter-clockwise spiral (as the animal sees it) and grows continuously, replacing wear. Occasionally the right tooth will also grow through the jaw; a few skulls with two tusks have been found.

Surface Characteristics

Color

Narwhals are countershaded, which means they are dark on top and light on the bottom. Newborn calves are dark blue-gray, and as they grow the back turns olive brown and they develop the leopard spotting pattern common in adults.

Fins and Fluke

Narwhals have no dorsal (back) fin, but they have an uneven ridge along the spine on the rear part of the back. The outer tip of each short flipper is curved upwards. The flukes are fan-shaped, with a deep notch.

Length and Weight

Adult males measure 4.6 meters (15 feet) and weigh 3,500 pounds. Adult females measure 4.0 meters (13 feet) and weigh 2,000 pounds.

Feeding

Narwhals feed in deep bays and inlets, where they find a good supply of Arctic cod, squid, and other food such as flatfish, pelagic shrimp, and cephalapods. At one time it was thought the tusk might be used to stir up bottom sediments in search of food. Other uses, however, seem to be more probable, since female narwhals are able to feed without a tusk.

Mating and Breeding

Males reach sexual maturity at 8-9 years, and females reach sexual maturity at 4-7 years of age. The gestation period is 15 months, and limited data suggest that the calving interval is one calf every 3 years. Calves measure 1.5 meters (5 feet) and weigh 180 pounds at birth. The calf stays with the mother up to 20 months. Narwhals breed in the spring, with mating usually occurring in mid-April, and the calf is born the following July. Calves are often born in deep bays and inlets. The function of the narwhal tusk as been a matter of some debate, but recent research has shown it to be related to mating activity. Many males have been found with broken tusks, and one male has been found with a tusk tip embedded in its skull. Narwhals have been seen with their tusks crossed, as if in a fencing match. Recent observations seem to support the theory that the tusk is used as a weapon by the males in battles over possession of females. This evidence, combined with data indicating a rapid growth of the tusk at sexual maturity in males, suggests a possible breeding function.

Range Map

Males reach sexual maturity at 8-9 years, and females reach sexual maturity at 4-7 years of age. The gestation period is 15 months, and limited data suggest that the calving interval is one calf every 3 years. Calves measure 1.5 meters (5 feet) and weigh 180 pounds at birth. The calf stays with the mother up to 20 months. Narwhals breed in the spring, with mating usually occurring in mid-April, and the calf is born the following July. Calves are often born in deep bays and inlets. The function of the narwhal tusk as been a matter of some debate, but recent research has shown it to be related to mating activity. Many males have been found with broken tusks, and one male has been found with a tusk tip embedded in its skull. Narwhals have been seen with their tusks crossed, as if in a fencing match. Recent observations seem to support the theory that the tusk is used as a weapon by the males in battles over possession of females. This evidence, combined with data indicating a rapid growth of the tusk at sexual maturity in males, suggests a possible breeding function.

Natural History

The narwhal is a deep-water cetacean, and has been known to dive to 1,200 feet. It has up to 4" of blubber under its skin, which is needed for protection in the cold arctic waters. Becoming trapped in forming ice is not uncommon; in Greenland such an entrapment is called a "savssat". The most sever savssat occurred in the winter of 1914-1915, when over 1,000 narwhals died in an entrapment. Other sources of danger include attacks by orcas (killer whales) and, rarely, walruses, and polar bears.

Status

Humans have valued the narwhal's tusk for many years. It is probably the origin of the myth of the unicorn, but the tusk and the narwhal were first associated in 1648 when Tulpius examined a stranded specimen in the British Isles. Through the Middle Ages the tusk was sold to cure epilepsy, strengthen the heart, induce perspiration, and buffer poison. A narwhal tusk was among the most prized possessions of Queen Elizabeth I. Narwhals are also important to many Eskimo cultures. Although the meat is used primarily for sled dogs, the skin is an important source of Vitamin C. This chewy delicacy is called "muktuk". Current population estimates in the Northwest Atlantic region are thought to be around 50,000, and worldwide estimates are not available. Dangers to the various populations currently exist. There are still over 1,000 narwhals killed each year between Canada and Greenland, which is thought to be above a sustainable level. Their habitat is being mined and drilled and already there are concerns about heavy metal levels in narwhal tissues.

Bibliography

- Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. & K. Laidre. 2006. Greenland's Winter Whales. Ilinniusiorfik.

- Jefferson, T.A., M.A. Webber, R.L. Pitman. 2015. Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, 2nd edition. Elsevier/AP.

- Leatherwood, S.L. and R.R. Reeves. 1983. The Sierra Club Handbook of Whales and Dolphins. Sierra Club Books, San Francisco.

- Perrin, W., B. Würsig, and J.G.M. Thewissen, Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. New York, NY: Academic Press, 2002

Acknowledgements

Illustrations courtesy Uko Gorter, copyright ©2017 all rights reserved.

FACT SHEETS MAY BE REPRINTED FOR EDUCATIONAL OR SCIENTIFIC PURPOSES

|